After listening to the feedback on the “Identifying Prowess in an SCA Musician” post, we’ve made a few changes to the checklist. I want to provide some definitions, elaborate on what is meant by some of the items, and provide some context for why this document exists in the first place. I also want to address a few other comments made about the list or its authors.

Why does this list exist?

Kasha and I are members of the Order of the Laurel in the Middle Kingdom. Both of us have expertise in European Music before 1600. As is widely known, the Order of the Laurel has meetings where we discuss who we want to recommend to the Crown as a potential member of the Order. (Quick pause to remind people that we don’t actually decide who is or isn’t let in; the Crown does that.) One of the aspects discussed is a candidate’s “prowess in their art.” Kasha and I noticed that the Order’s discussions about potential music candidates could be much improved if we had some kind of criteria list–or something–to work with. We created the list primarily as a way to have common ground when discussing candidates. When an art is not your special area of expertise, it can be difficult to know how to evaluate others. For example, Carol has often found herself looking at sewing projects and thinking, “This is pretty! I think it’s period! I like it!”, which is not a responsible way to recommend a candidate to the Crown. We would rather have a sewing expert tell us what to look for — stitch size, appropriate materials, etc. We hope the list we’ve created will help non-musicians in a similar way.

Kasha and I think analytically, so a checklist was a natural fit. (I’d love to hear other ways of doing the same work, though.) It is not intended to cover all candidates. It does not preclude specialization. What it does do is allow us to have discussions like “Lord Lutesinger is not very knowledgeable in repertoire before 1400 and doesn’t sight-read consort music as well as we’d normally expect, but more than makes up for it with his depth of knowledge in 15th and 16th century lute repertoire, his vocal and lute technical skill, and his championing of the lute in the Society”. I really want to have that discussion and not “Lord Lutesinger plays his lute at many events. It sounds good,” especially when this ‘Lutesinger’ doesn’t actually read lute tablature and just plays chords when they are written in for him on top of the music.

If we were going to put together a reference document, we really wanted to make it something everyone can see. For many reasons, people should be able to see this. For one, I think it’s only fair that we if this list is being used by the Laurels (even if it’s only some of them) that everyone should be allowed to view it, work with it, and critique it. Second, I think I would have found it helpful when I was still working toward peerage. I could see myself using this list with future apprentices to generate interesting discussions. I imagine that would be true for other people too.

Why is it so broad?

While I’ve said that the list doesn’t preclude specialist candidates, it does assume that a default hypothetical candidate is someone with a broad knowledge base. Some of that is because Kasha and I have a broad knowledge base. We enjoy, perform, and study music from a broad range of SCA period. But, more than that, the basic job of a Laurel is to be able to evaluate the prowess of candidates in your field. If you’re knowledgeable in only a very specific area, there are fewer candidates you are able to effectively evaluate.

But doesn’t that mean you’re only encouraging one kind of music candidate?

I don’t think so? I think a variety of styles of musician can fare well on this checklist. Any criteria list can be misused, but I think that risk is worth the potential gain of more fruitful discussion.

What are the ‘moderate changes’?

The main change is adding a category between “Proficiency with the Elements of Historical Music” and “In-depth Understanding of Historical Music.” The first category can be intimidating because it has the words “all” and “competent”. After receiving feedback from many people, weI do think there are some ‘must have’ items, but they need to be clearer and easier to meet than what we’d had in the first version of the document.

In the new version, the first section represents our “red flag” items, where if a candidate could not do any one of the items in that section we’d have serious doubts they were ready for the scrutiny of the Order. I spent some time trying to apply the “”Basic Proficiency”” section to my own SCA career, and came to the conclusion that I’d more or less completed it in about a year or two of playing in the SCA. (I feel obliged to mention that during that time I’d taken over the local choir, which encouraged me to work on quite a few of the items the list.) I didn’t have everything in the Performance subsection because I started playing recorder after joining the SCA and our local group Cynnabar didn’t have a regular sight-reading group. I expect that there are quite a few people in the SCA who can meet a lot or all of the material in the new “Basic Proficiency” section now.

The new second category, “Greater Proficiency with the Elements of Historical Music”, includes the things that we’d really like to see in all candidates, but wouldn’t necessarily disqualify a candidate if they couldn’t do every single one–especially if that candidate were very especially skilled in a certain area.

The rest is mostly the same.

What do you mean by ‘competent’?

Speaking for myself, competence boils down to three things:

- Being able to speak intelligently about a given topic.

- Being able to recognize when someone is or isn’t speaking intelligently about a given topic.

- Being able to prepare a class on anything on a given topic in a week where you have some free evenings and a weekend to prepare.

In practice, this means that at any given moment, you’d have a sentence or two to say about any of the topics on the list, and your sentence or two would be reasonable assertions.

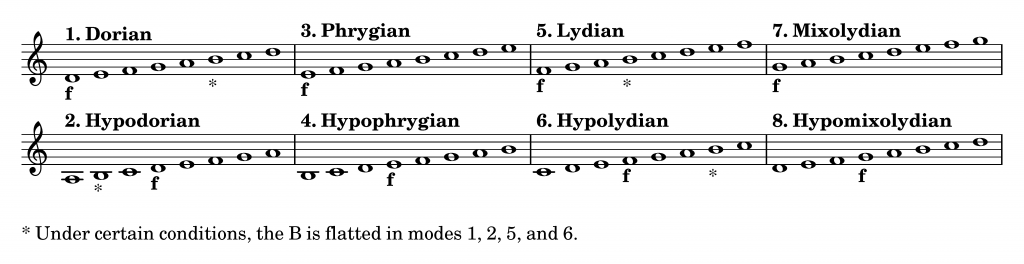

For example for, “Outline the history of musical composition practice from 900-1600, tracing developments in modes/scales, harmonic motion, rhythmic rules, and expressive devices,” I might say something like:

“From 900 to 1600 the major shift was from solely monophony to monophony and polyphony. Over that time we can see the development of music notation as we know it now, starting from glorified memory aids to formal systems of notating pitch, rhythm, and even sometimes ornamentation. The relationship between modes and composition across period was existent but also contradictory and hard to explain. Pitch notation settled into more-or-less how we know it today fairly early in period. Rhythmic notation continued evolving across period, and differs from modern notation in that it was divisive rather than additive. (That is, in period music, we take a big beat–the tactus–and divide it into groups of usually 2 or 3 to get smaller note values. As opposed to today where we talk about the number of quarter notes in a half note, etc.) Music moved in the direction of conscious harmonic motion across period, but wasn’t discussed and thought about as such during period. Composition of polyphony primarily involved making sure the lines followed certain rules.”

This is not super detailed, but it is more-or-less correct. I couldn’t give an hour-long class on any of these sentences tomorrow, but I could by next weekend. If you asked for sources to back up these claims, I could give them to you. (For the bit about modes, for instance, the Early Music Sources video is great.) I want to see this level of competence in candidates, and I do know quite a few people who can do this, both in the order and not.

But I just don’t care about a lot of this stuff…

Hey, you do you! I’m happy to play and make music with people at all levels of ability and interest. You are absolutely still valued. But, like, you can’t ethically claim to be an expert in period music in the Society (in the Middle Kingdom at least) if you wouldn’t fare well on this checklist and don’t want to make the effort to do more of the things listed.

It’s not a value or character flaw to not care about something. There are plenty of skilled musicians I play with who don’t want to do this kind of work. That’s fine. I’m thrilled I get to play with them.

This checklist isn’t doable by non-professionals / non-rich people

Um… my degree is in Electrical Engineering. Aaron Drummond–my husband and fellow Music Laurel– has his degree in Computer Science. It’s true that I do teach piano for pay, but that’s based primarily on my childhood piano education and, honestly, patience. We are doing this as dedicated amateurs, with all the benefits and detriments that offers.

Regarding the cost barrier, if you look at the list, there is no mention of owning period reproduction instruments or regular private lessons with a period music focus or attending prestigious workshops. Meeting the requirements of the list involves taking SCA classes in historical music when you can (at Pennsic you can take quite a few, and if you’re in the Middle Kingdom, St. Cecilia at the Tower has a whole day’s worth), doing some music stuff in your free time a few times a week, and listening to fair number of recordings. Books about music history and scores are available for free online or at the library. If you love this stuff, it really isn’t a hardship unless you have no free time or energy.

Now you might notice that musician Laurels often do have period instruments and do go to prestigious workshops, and sometimes do spend money and time on private lessons. This happens because saving up to buy a period instrument or go to a workshop is worth it if you’re spending a lot of time on this stuff anyway.

I have a degree in music and I don’t fare well on this checklist

Kasha speaking: This doesn’t necessarily surprise me, since university music students and SCA musicians are typically taught different skills.

As an SCA musician who also happens to have a Bachelor of Arts in Music (with a Composition Emphasis) and a Master of Arts in Vocal Performance, I can talk a little bit about what I learned in school and what I learned in the SCA. The primary difference is this: At the university, we are taught from a musical tradition that emphasizes the Common Practice Period (about 1600-1900) and that treats music as a craft largely divorced from its cultural context. In the SCA, we study music written and/or performed before 1600 and think about it from the perspectives of historians and sociologists.

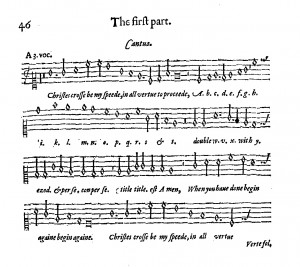

Here’s what I learned about medieval and Renaissance music in my university music program (other people’s experiences may differ). During my undergraduate studies, I took a year-long music history class that covered Western music from about 900-2000. We spent less than a semester on the medieval and Renaissance periods combined. In graduate school, I took a one-semester class on Renaissance music. Because I was interested in it, I also opted to join my college’s chamber choir, which sometimes performed Renaissance pieces (or modern arrangements of them). And in one graduate school class, my teacher played a piece of monody as an example of a type of music “we were probably unfamiliar with”. As far as I can recall, that is the sum total of my engagement with pre-17th-century music as a music major. On the contrary, most of the focus was on performance technique for Common Practice Period pieces, the teaching and arranging skills I would use if I chose to be a middle- or high-school band director, and — since I was a composition major — the extended techniques invented and used by 20th-century composers. When I graduated with my B.A., I could name a few medieval composers, had a vague idea that music before the Common Practice Period “developed” from Gregorian chant into English madrigals, and enjoyed listening to music composed by Josquin and Dufay (though I couldn’t describe how those pieces were put together).

I don’t want to downplay the privileges I have as a result of my education. As a music student, I gained experience listening critically to music and talking about what I’d heard and sung. I also learned about what kind of resources are available for researchers, gained experience playing in ensembles, and became proficient with music notation software. These skills have been valuable to me as I have studied music in the SCA (though I absolutely believe they can be learned outside the university, as well).

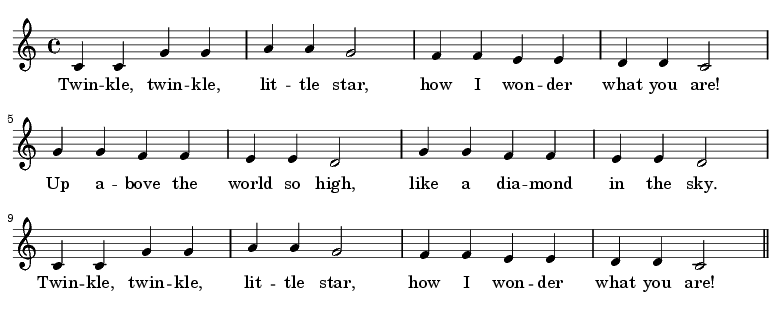

After joining the SCA, I began to study medieval and Renaissance music independently. I searched the internet for journal articles, listened to Dufay compositions on auto-repeat until I could sing along, went to the library for books of medieval poetry, experimented with composing my own motets for arts & sciences competitions, and learned pieces inside-out by transcribing them. It is in the SCA that I have had opportunities to lead and select repertoire for ensembles, play from period notation, attend day-long music history symposia (we call them “SCA events”), and arrange pieces for real performance by real performers. I’ve been forced to think like a historian, attempting to get inside the minds of people from another place and time and recreate their music in ways they might recognize, rather than using my personal taste as the primary consideration in musical decision-making. Most importantly, I’ve spent hours playing medieval music with other SCA musicians and afterward, talking with them about what we’ve played and listened to. We share helpful blogs, sources for musical material, and the names of favorite performers and instrument-makers.

While I do know a handful of SCA musicians who have also studied music formally at a university, most of the people I regularly make music with have not done so, and I consider many of them to be more knowledgeable than I am (and certainly better technicians!). We are teachers and students for each other, and to me, this is the most exciting part of being in the SCA.

In summary, I learned a lot in my music program, and I’ve learned a lot in the SCA — just about different things. Not only is this okay, it’s to be expected!

You just want to keep people out of the Order now that you’re in / You aren’t doing the work needed to help people meet your ‘standards’

Back to Jadzia: Um… just no. I’d feel insulted if the assertion wasn’t ridiculous. My SCA career has been spent making it easier for people to develop this level of prowess. More importantly, in the Middle Kingdom there are people who are meeting these standards.

Without a doubt, I want the bar in music in the SCA to continue to get higher. The SCA has the potential to do some interesting performance experimentation that even super skilled modern Early Music world people can’t because of the constraints of working in that world. The potential for doing interesting musical stuff is really motivating for me. That said, I care about how the standard rises. I want it to rise because it’s easy to improve when there are many skilled, generous musicians to play with. I want it to rise because people believe getting more skilled and more knowledgeable is both doable and worthy.

. Many pieces that fit a soprano recorder also fit the alto recorder, and those pieces are all written alto “octave up”.

. Many pieces that fit a soprano recorder also fit the alto recorder, and those pieces are all written alto “octave up”.